Full disclosure; I have never read a memoir.

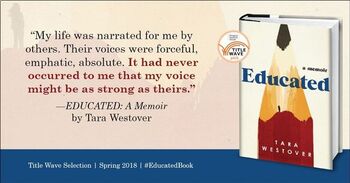

I had been educated in the rhythms of the mountain, rhythms in which change was never fundamental, only cyclical. The same sun appeared each morning, swept over the valley and dropped behind the peak. The snows that fell in winter always melted in the spring. Our lives were a. Educated is a testimony of following one’s ambitions and dreams while overcoming overwhelming obstacles and hardships. It is an inspiring story of the drive for self-realization and while overcoming doubts, guilt, self-worth, and unhealthy family ties and beliefs.

I know, I know. How can I taut myself as a reading buff and have never even attempted to read someone else’s life story. It’s atrocious, to say the least.

Well, here’s a good selling point for Educated: I generally loathe nonfiction, and it took a reading challenge to get me to select a genre I’m not particularly interested in. I am so glad I did. Pushing myself to read Tara Westover’s grippingly powerful story was one of the best reading decisions I’ve made this year. If you give any book a chance, it should be this one.

Westover came from a family of fundamentalist Mormons living on the outskirts of society in Idaho. Her father Gene, is depicted as a manic man, susceptible to fits of religious passion, extreme paranoia involving government conspiracies and staunch opposition to any agency that could be aligned with the government (including hospitals and public schools). Because of his mounting resistance to such organizations, Gene pulled his older children from school, refused to document the births of his three youngest children, and under no circumstances would allow his family to go to a hospital (on multiple occasions, such instances could have been life or death). This maniacal behavior was later attributed to bipolar disorder, as confirmed to Westover by her mother.

At sixteen, Westover made the choice to take the ACT, and though she’d never received formal, academic based homeschooling, attempted to obtain acceptance into a university. Two of her older brothers who had also strayed from their family’s flock to pursue higher education, acted as Westover’s support network for this endeavor. Westover was accepted to Brigham Young University.

Canvas for mac. Entering the environment of a university was equivalent to stepping into a completely different world for Westover. Though BYU was a private, Mormon school, Westover found herself amongst a throng of “gentiles” as her father would dub them; people who drank Diet Coke, washed their hands after using the restroom, and women who shamelessly bared their legs and shoulders for all the world to see.

From this point onward, it was a constant and tiresome struggle for Westover to find equilibrium with her two worlds. Her family, who were as fast to lend surprising support (such a helping finance school and making a surprise visit to Harvard), were just as quick to be cruel and make their love conditional (in order for Tara to be allowed back into their family, she had to “stop lying” about her older brother Shawn’s physical abuse). The ping-ponging and instability of such a family had the expected effect; eventually, Westover began suffering from panic attacks and regular breakdowns. With the insistence of a friend, Westover sought counseling services and began to see the abuse she had been enduring for what it was.

Going above and beyond what anyone would have expected, Tara Westover continued on to obtain her PhD from Cambridge University. As Westover puts it, she found herself through education.

As a woman, an educator, and an advocate for learning and literacy, I was so overwhelmed and in awe of Westover’s perseverance over her background, her abusive, manipulative, and fundamentalist family, and all of the cultural handicaps that could very well have prevented her from pursuing an education.

Westover’s internal struggle of trying to leave the manipulative relationships with her father, mother and brother, while remaining loyal to them was frustrating and heartbreaking to read, but so realistic. At one point in the book, she describes it as a kind of Stockholm Syndrome – being inexplicably devoted to those that hurt her the most.

But this isn’t purely a story about irrational familial obligations, or even about finding the passion and tenacity to blaze a different path to higher education. It’s also a story about the tragedy of the marginalized population in the middle of the United States. I found myself wondering how it could be possible for a whole family to be ignored by protective agencies such as CPS (Child Protective Services) after multiple instances of endangerment, involving two extreme car crashes, a severe burning, and multiple head injuries that resulted in obvious concussions that cause other neurological problems because they were untreated. How were they overlooked? How, in this day and age, is it possible for anyone to be as good as invisible?

With her story, Westover has opened up a can of worms by bringing attention to the bizarre and treacherous place she called home for so many years. But she has also brought to light the endurance of the human spirit.

I truly hope you check out this memoir and share your thoughts with our reading community!

Happy & healthy reading!

Alexis

If this sounds like your kind of read, you can get a copy here:

Other memoirs that might peak your interest are:

I know this is an adult best seller, but would it be a could book to put in middle school. I have a few memoirs like The Glass Castle, and kids love it.

Comments are closed.

Tara Westover was raised by fundamentalist Mormon survivalists in the mountains of Idaho. She never attended school and was home-schooled only when there was time after work in the family salvage and herbalist business. In her memoir Educated, she tells the story of how at 16 she taught herself enough math and grammar to get accepted into Brigham Young University and went on to receive her PhD from the University of Cambridge, at the cost of her relationship with her family. The following is an excerpt from the book.

American history was held in an auditorium named for the prophet Joseph Smith. I’d thought American history would be easy because Dad had taught us about the Founding Fathers — I knew all about Washington, Jefferson, Madison. But the professor barely mentioned them at all, and instead talked about “philosophical underpinnings” and the writings of Cicero and Hume, names I’d never heard.

In the first lecture, we were told that the next class would begin with a quiz on the readings. For two days I tried to wrestle meaning from the textbook’s dense passages, but terms like “civic humanism” and “the Scottish Enlightenment” dotted the page like black holes, sucking all the other words into them. Batteries for apple mac. I took the quiz and missed every question.

That failure sat uneasily in my mind. It was the first indication of whether I would be okay, whether whatever I had in my head by way of education was enough. After the quiz, the answer seemed clear: it was not enough. On realizing this, I might have resented my upbringing but I didn’t. My loyalty to my father had increased in proportion to the miles between us. On the mountain, I could rebel. But here, in this loud, bright place, surrounded by gentiles disguised as saints, I clung to every truth, every doctrine he had given me. Doctors were Sons of Perdition. Homeschooling was a commandment from the Lord.

Failing a quiz did nothing to undermine my new devotion to an old creed, but a lecture on Western art did.

The classroom was bright when I arrived, the morning sun pouring in warmly through a high wall of windows. I chose a seat next to a girl in a high-necked blouse. Her name was Vanessa. “We should stick together,” she said. “I think we’re the only freshmen in the whole class.”

The lecture began when an old man with small eyes and a sharp nose shuttered the windows. He flipped a switch and a slide projector filled the room with white light. The image was of a painting. The professor discussed the composition, the brushstrokes, the history. Then he moved to the next painting, and the next and the next.

Then the projector showed a peculiar image, of a man in a faded hat and overcoat. Behind him loomed a concrete wall. He held a small paper near his face but he wasn’t looking at it. He was looking at us. I opened the picture book I’d purchased for the class so I could take a closer look. Something was written under the image in italics but I couldn’t understand it. It had one of those black-hole words, right in the middle, devouring the rest. I’d seen other students ask questions, so I raised my hand.

The professor called on me, and I read the sentence aloud. When I came to the word, I paused. “I don’t know this word,” I said. “What does it mean?”

There was silence. Not a hush, not a muting of the noise, but utter, almost violent silence. No papers shuffled, no pencils scratched.

The professor’s lips tightened. “Thanks for that,” he said, then returned to his notes.

I scarcely moved for the rest of the lecture. I stared at my shoes, wondering what had happened, and why, whenever I looked up, there was always someone staring at me as if I was a freak. Of course I was a freak, and I knew it, but I didn’t understand how they knew it.

When the bell rang, Vanessa shoved her notebook into her pack. Then she paused and said, “You shouldn’t make fun of that. It’s not a joke.” She walked away before I could reply.

I stayed in my seat until everyone had gone, pretending the zipper on my coat was stuck so I could avoid looking anyone in the eye. Then I went straight to the computer lab to look up the word “Holocaust.”

I don’t know how long I sat there reading about it, but at some point I’d read enough. I leaned back and stared at the ceiling. I suppose I was in shock, but whether it was the shock of learning about something horrific, or the shock of learning about my own ignorance, I’m not sure. I do remember imagining for a moment, not the camps, not the pits or chambers of gas, but my mother’s face. A wave of emotion took me, a feeling so intense, so unfamiliar, I wasn’t sure what it was. It made me want to shout at her, at my own mother, and that frightened me.

I searched my memories. In some ways the word “Holocaust” wasn’t wholly unfamiliar. Perhaps Mother had taught me about it, when we were picking rosehips or tincturing hawthorn. I did seem to have a vague knowledge that Jews had been killed somewhere, long ago. But I’d thought it was a small conflict, like the Boston Massacre, which Dad talked about a lot, in which half a dozen people had been martyred by a tyrannical government. To have misunderstood it on this scale — five versus six million — seemed impossible.

Educated Memoir Review

I found Vanessa before the next lecture and apologized for the joke. I didn’t explain, because I couldn’t explain. I just said I was sorry and that I wouldn’t do it again. To keep that promise, I didn’t raise my hand for the rest of the semester.

A Memoir Educated By Tara

From the book Educated by Tara Westover. Copyright © 2018 by Tara Westover. Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Sign up for Inside TIME. Be the first to see the new cover of TIME and get our most compelling stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Thank you!

For your security, we've sent a confirmation email to the address you entered. Click the link to confirm your subscription and begin receiving our newsletters. If you don't get the confirmation within 10 minutes, please check your spam folder.Educated Memoir Summary

Educated A Memoir Summary

EDIT POST

Comments are closed.